Black Oil Beetle - Meloe proscarabaeus

During our walk in the summer along the Gower coast from Oxwich to Pitton Cross we came across 3 Black Oil Beetles, Meloe proscarabaeus. I often found them at this time of year along this stretch of the Welsh coast. The cliff top path is flanked by wide and unimproved grass verges dotted with gorse and wind structured blackthorn shrubs. Maybe the path itself allows easier overs action of these weird looking beetles, but once seen it’s difficult to ignore the large black lumbering insect going about it’s business of ensuring the survival of the next generation.

It’s common name of Black Oil Beetle is very apt, as they are black, but when the sun hits the body it can have a blue-violet sheen. Whilst this doesn’t make it a beauty, it does add it’s its charisma. M. proscarabaeus has a roughly square-shaped thorax, which has an almost square base with a very small rounded tooth at it’s base. It is these characteristics of the thorax that helps to differentiate it from the similar Violet Oil Beetle - Meloe violaceus. This can be easy to miss because the thorax appears to be small as your eyes are drawn to the hugely extended abdomen, which seems to be impossibly swollen. So swollen in fact that it waddles along the ground instead of walking.

Not surprisingly this is a flightless Beetle, and the elytra are small and stubby in appearance. Males have kinked antennae., and the females have slightly-kinked antennae. It’s appearance is not the only unusual fact about the Black Oil Beetle. It’s life cycle as a whole is fascinating and unconventional to say the least. After mating the female searches out a suitable place to dig a burrow to lay her eggs. This maybe while I often see them near the path, as she is searching for a patch of bare ground to start the burrow. Once a suitable site has been found she lays around a 1000 eggs. When the eggs hatch the larvae, called traungulia leave the burrow and climb up only flowers heads, where they wait for a passing bee. The triungulia have a tactic to increase the chance of hits hint a ride by cooperating together and create pyramid forming living pyramids so as to enable them to hitch a lift on solitary bees visiting the flowers. It is this unsuspecting solitary bee that is the main target fo the triungulin, and is necessary for the next stage in it’s life cycle.

Once a bee visits the flower the tiny triungulin attempts to hitch a ride, and if successful is transported to the bees nest. It they are lucky and have attached themselves to the right bee, because not all bees are ‘equal’ in the eyes of an oil beetle, it will detach itself from the host and secrete itself in the nest. Once in the next the triungulin will transform into a grub-like larvae and then eat the eggs of the host bee, along with the pollen stores. Once fully grown the larva then pupates and adult beetle overwinters within the solitary bee’s nest , ready to emerge the following spring to coincide with the breeding cycle of the host bees and start the parasitic process all over again.

The numbers of oil Beetles has seen a significant reduction in numbers. This is linked to loss of habitat and also because of the reduction in the umber of solitary bees. It is this intimate and dependent relationship on solitary bees that can have a big impact on it’s breeding success. Any changes or loss of habitat means less foraging and flowers for bees, which in turn reduces the breeding success of bees. Fewer bees then mean fewer Oil Beetles. The maths is simple. The ideal habitat for Oil Beetles is grassland and heath rich in wild flowers. And often these care found around coastal areas, hence i suppose the frequency I come across whilst limboing along the coast paths in Wales. They can be found from February through to June. According to Bug Life the Welsh and Gower coasts offers the most likely areas to find the Black Oil Beetle. Because of this decline the Black Oil Beetle is on a number of Biodiversity Priority Lists including Natural England England (http://publications.naturalengland.org.uk/file/6518755878240256) , So if you do see one you can report it via BugLife.com or iReord. So go searching

It’s common name of Black Oil Beetle is very apt, as they are black, but when the sun hits the body it can have a blue-violet sheen. Whilst this doesn’t make it a beauty, it does add it’s its charisma. M. proscarabaeus has a roughly square-shaped thorax, which has an almost square base with a very small rounded tooth at it’s base. It is these characteristics of the thorax that helps to differentiate it from the similar Violet Oil Beetle - Meloe violaceus. This can be easy to miss because the thorax appears to be small as your eyes are drawn to the hugely extended abdomen, which seems to be impossibly swollen. So swollen in fact that it waddles along the ground instead of walking.

Not surprisingly this is a flightless Beetle, and the elytra are small and stubby in appearance. Males have kinked antennae., and the females have slightly-kinked antennae. It’s appearance is not the only unusual fact about the Black Oil Beetle. It’s life cycle as a whole is fascinating and unconventional to say the least. After mating the female searches out a suitable place to dig a burrow to lay her eggs. This maybe while I often see them near the path, as she is searching for a patch of bare ground to start the burrow. Once a suitable site has been found she lays around a 1000 eggs. When the eggs hatch the larvae, called traungulia leave the burrow and climb up only flowers heads, where they wait for a passing bee. The triungulia have a tactic to increase the chance of hits hint a ride by cooperating together and create pyramid forming living pyramids so as to enable them to hitch a lift on solitary bees visiting the flowers. It is this unsuspecting solitary bee that is the main target fo the triungulin, and is necessary for the next stage in it’s life cycle.

Once a bee visits the flower the tiny triungulin attempts to hitch a ride, and if successful is transported to the bees nest. It they are lucky and have attached themselves to the right bee, because not all bees are ‘equal’ in the eyes of an oil beetle, it will detach itself from the host and secrete itself in the nest. Once in the next the triungulin will transform into a grub-like larvae and then eat the eggs of the host bee, along with the pollen stores. Once fully grown the larva then pupates and adult beetle overwinters within the solitary bee’s nest , ready to emerge the following spring to coincide with the breeding cycle of the host bees and start the parasitic process all over again.

|

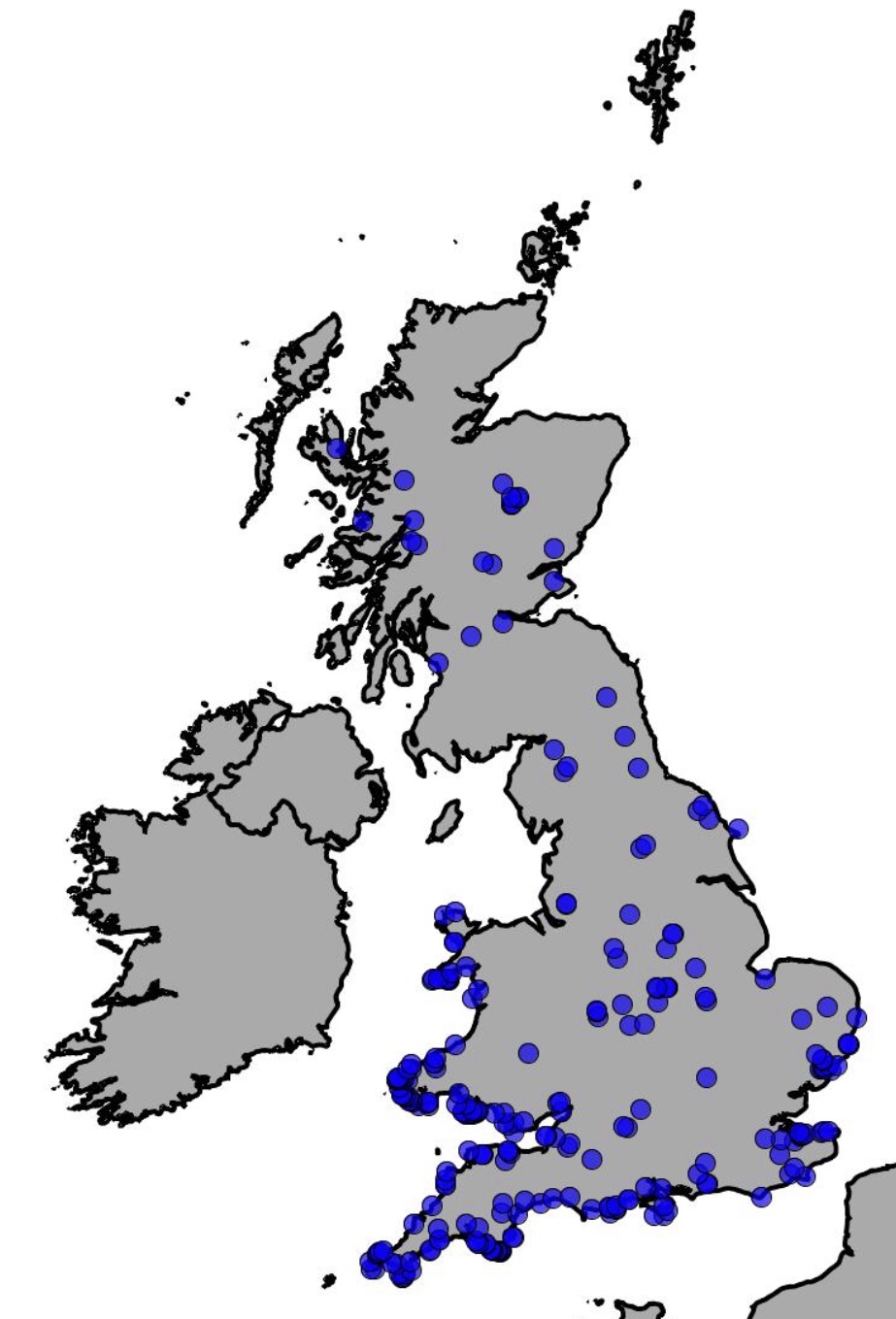

| NBN Distribution Map. |

The numbers of oil Beetles has seen a significant reduction in numbers. This is linked to loss of habitat and also because of the reduction in the umber of solitary bees. It is this intimate and dependent relationship on solitary bees that can have a big impact on it’s breeding success. Any changes or loss of habitat means less foraging and flowers for bees, which in turn reduces the breeding success of bees. Fewer bees then mean fewer Oil Beetles. The maths is simple. The ideal habitat for Oil Beetles is grassland and heath rich in wild flowers. And often these care found around coastal areas, hence i suppose the frequency I come across whilst limboing along the coast paths in Wales. They can be found from February through to June. According to Bug Life the Welsh and Gower coasts offers the most likely areas to find the Black Oil Beetle. Because of this decline the Black Oil Beetle is on a number of Biodiversity Priority Lists including Natural England England (http://publications.naturalengland.org.uk/file/6518755878240256) , So if you do see one you can report it via BugLife.com or iReord. So go searching

Comments

Post a Comment